Demonetisation of High Denomination Notes in India

Demonetisation of currency is a radical monetary step in which a currency unit’s status as a legal tender is declared invalid. This is usually done whenever there is a change of national currency, replacing the old unit with a new one. Such step, for example, was taken when the European Monetary Union nations decided to adopt Euro as their currency. However, the old currencies were allowed to convert into Euros for a period of time in order to ensure a smooth transition though demonetization. Zimbabwe, Fiji, Singapore and Philippines were other countries to have opted for currency demonetization.

Demonetisation of currency is a radical monetary step in which a currency unit’s status as a legal tender is declared invalid. This is usually done whenever there is a change of national currency, replacing the old unit with a new one. Such step, for example, was taken when the European Monetary Union nations decided to adopt Euro as their currency. However, the old currencies were allowed to convert into Euros for a period of time in order to ensure a smooth transition though demonetization. Zimbabwe, Fiji, Singapore and Philippines were other countries to have opted for currency demonetization.

India’s currency notes are printed in Bharatiya Reserve Bank Note Mudran Private Limited at Mysuru and Salboni (near Mednapore in West Bengal), and Security Printing and Minting Corporation of India Limited’s Currency Note Press at Nashik and Bank Note Press at Dewas.

India Security Press, Nashik, and Security Printing Press, Hyderabad, print non-currency material such as passport, visa, IT refund orders, identify cards for higher officials, and warrants, among other things.

Demonetisation in India

In India’s case, the move has been taken to curb the menace of black money and fake notes by reducing the amount of cash available in the system. It is also interesting to note that this was not the first time the Government of India has gone for the demonetization of high-value currency. It was first implemented in 1946 when the Reserve Bank of India demonetized the then circulated ₹1,000 and ₹10,000 notes. The government then introduced higher denomination banknotes in ₹1,000, ₹5,000 and ₹10,000 in a fresh avatar eight years later in 1954 before the Morar Ji Desai government demonetized these notes in 1978. The government’s move to demonetize, even then, was to tackle the issue of black money economy, which was quite substantial at that point of time. The move was enacted under the High Denomination Bank Note (Demonetisation) Act, 1978. Under the law all ’high denomination bank notes’ ceased to be legal tender after January 16, 1978. People who possessed these notes were given till January 24 the same year a week’s time to exchange and high denomination bank notes.

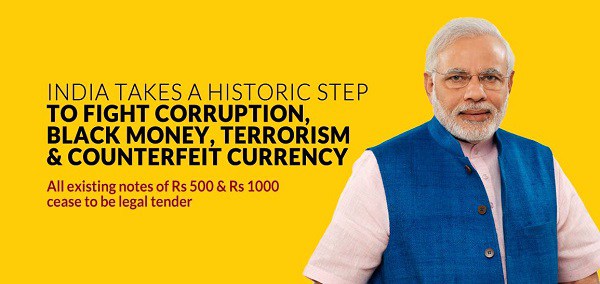

In a recent move Prime Minister Narendra Modi hit hard on corrupt bureaucrats, politicians, and business class, terrorists’ group, smugglers, drug traffickers, hawala traders, black marketers and many others engaged in unlawful activities by announcing on November 8, 2016 that ₹500 and ₹1,000 currency notes would no longer be legal tender money. The people were given chance either to exchange the old currency with new through banks/post officers or deposit the same in their accounts up to December 30, 2016 with a rider that any deposit of more than ₹2.50 lakh would be scrutinized by the income tax authorities. All notes in lower denomination of ₹100, ₹50, ₹20, ₹10, ₹5, ₹2, and ₹1 and all coins continued to be valid, and new notes of ₹2,000 and ₹500 were introduced. There was no change in any other form of currency exchange be it cheque, DD, payment via credit or debit cards etc. The step was aimed at curbing the ’disease’ of corruption and black money which had taken deep roots.

The main difference between previous drivers of demonetization previous drives of demonetization and the current one is that currency of higher denomination was barely in circulation in 1948 or 1978, unlike the ₹500 and ₹1000 note in 2016. There is a world of difference, however, between the demonetization of 1978 and now. The middle class in 1978 was not only sparse but also lived mostly with in the modest income bracket. A large section of this class had no access to high denomination currency notes, that began with ₹1,000 and went up to 10,000. Much of the currency notes. Even the common people with meager income possess ₹500/1000 notes.

According to the Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI) annual report, 2016, the total value of currency in circulation is ₹16.4 lakh crore. Of this, 38.6 percent or ₹6.3 lakh crore is in the form of ₹1,000 notes. Another 47.8 percent or ₹7.8 lakh crore is in the form of ₹500 notes. This means that over 86 percent of Indian currency will be withdrawn and needs to be exchanged before it can be used.

Objectives of Demonetisation

Officially the current demonetization has been taken with the following objectives:

- to track fake currency

- to cut of the supply line money, arms and ammunition to terror funding

- to transform Indian economy into a cashless economy

- to bring tax evasion to halt

- to unearth and curb the black money

- to curb illegal and unethical business activities such as the black marketing, food adulteration, marketing of spurious goods, human trafficking, smuggling of gold and drugs

Benefits of Demonetisation

Looking ahead, the best course of action would be to consolidate on the benefits of demonetization. On the currency management front, regular upgrades of currency notes along with a complete withdrawal of the old series may have been good practice in the past. But this may not be required now thanks to the high-tech features built into the new notes. Still, periodic disruption will help fight counterfeiting and hoarding.

Impact of Demonetisation on Economy

In a bid to clampdown on black money, the government withdrew ₹500 and ₹1,000 notes from circulation with immediate effect. Reserve Bank of India (RBI) data suggests that the proportion of ₹500 and ₹1000 notes were 86.4% of total value of notes in circulation of March 31, 2016, amounting to ₹14 trillion. The growth rates in these notes were 76% and 109% respectively in the last five years versus overall currency in circulation going up by 40%, points out of Citigroup note. Experts visualized the following impact of demonetization on the economy in the near future:

- Which citizen will be inconvenienced in the short term, this is a big medium-term positive in the government’s effort to crack down on black money and corruption.

- In the short – run GDP growth rate may decline by 0.1-0.2 percentage points, but in the long run the net impact of demonetization will be positive.

- As the old currency notes are deposits with banks, bank deposit growth will witness a pickup and currency in circulation will moderate a positive for banking sector liquidity.

- As rural house-holds open new bank accounts to deposit accounts to deposit old note, this may also end up giving a boost to the government’s financial inclusion thrust.

- Since black money played a role in real estate transactions, this crackdown is very likely to hurt the real estate market, which is already reeling under high inventory in top tier cities such as Mumbai and Delhi.

- As some of the black money is brought under legitimate channels, the government’s tax revenue collection will get a boost.

- There could be an immediate increase in bank deposits if some of the holders of these old notes decide to deposit them rather than exchanging them for new notes. Currency in circulation might decline substantially if heightened security forces people with unaccounted for cash to not exchange/deposit. The base money goes down in that case but the increase in money multiplier (because of a higher deposit to currency ratio) might mitigate the impact on overall money supply.

- If money supply declines temporarily because of these measures, then assuming no immediate change in velocity of circulation, we could either see some deflationary tendencies or lowering of real demand (economic activity). The impacts could be different depending upon sectors – deflationary in some while contractionary in other. This is a short-term risk for the economy.

- The move generally bodes well for the inflation outlook since black money was associated with higher inflation. However, it is likely to hurt near-term consumption demand.

Impact of Demonetisation on Black Money

Dr. Bibek Debroy, member NITI Aayog, categorized the black money as ’single black’ and ’double black’. The ’Single black’ is when the activity is not illegal but the persons using this type of money have not paid taxes, while the ’double black’ is that type of money which is used to generate income through illegal activities crimes, trafficking, extortions etc.

According to Dr. Debroy, out of ₹14 lakh crore, currency in the form of ₹500 and ₹1000, probably something like ₹4 lakh crore, may be black money. He explains,” Let’s assume that out of ₹4 lakh crores, ₹2.5 lakh crore is single black and ₹1.5 lakh crore is double black. So, ₹1.5 lakh crore is roughly 10 percent of ₹14 lakh crores. This is completely destroyed. On Single black - ₹2.5 lakh crore – I think a large part of it will come back into the system. Of the remaining ₹10 lakh crore, ₹8 lakh crore is just probably transaction-related. This cash temporarily goes out of the system, but it eventually comes back into the system. The remaining ₹2 lakh crore is what the people were sitting on. This is not illegal. This ₹2 lakh crore is unproductive for the people holding on to it and for the system. This comes into the system. In the short-term of course there is impact – macro and sectoral impact. But, in the slightly medium-term, several things happen through RBI and outside RBI. The government and the banking system have more resources. The government can spend this extra money on various public goods and services including infrastructure, and the lenders can lend more. So, wealth is transferred from relatively rich to relatively poor in the process”.