Alcoholic Hepatitis

Table of Contents

Introduction

Alcoholic hepatitis is liver inflammation due to excessive consumption of alcohol. Alcohol has long been associated with serious liver diseases such as hepatitis - inflammation of the liver. But the relationship between drinking and alcoholic hepatitis is complex. Only a small percentage of heavy drinkers develop alcoholic hepatitis, yet the disease can occur in people who drink only moderately or binge just once. And though damage from alcoholic hepatitis often can be reversed in people who stop drinking, the disease is likely to progress to cirrhosis and liver failure in people who continue to drink. For them, alcoholic hepatitis may be fatal.

Researchers are learning more about how and why alcoholic hepatitis occurs, but less is known about how to treat alcoholic hepatitis effectively. Anyone with alcoholic hepatitis must avoid alcohol and other substances that harm the liver. When damage is so severe that the liver is unable to function, a liver transplant may be an option.

Signs and Symptoms

Mild forms of alcoholic hepatitis may not cause noticeable problems, but as the disease becomes more advanced and the liver more damaged, signs and symptoms are likely to develop. These may include:

-

Loss of appetite

-

Nausea and vomiting, sometimes with blood

-

Abdominal pain and tenderness

-

Yellowing of the skin and whites of the eyes (jaundice)

-

Fever

-

Abdominal swelling due to fluid accumulation (ascites)

-

Mental confusion

-

Fatigue

These symptoms may vary, depending on the severity of the disease, and are likely to become worse after a bout of binge drinking.

Causes

The liver is the body’s workhorse. It performs hundreds of vital functions, including processing most nutrients, producing bile and substances that help the blood clot, and removing drugs, alcohol, and other harmful substances from your bloodstream. Although the liver has a great capacity for regeneration, its constant exposure to toxins can cause serious - and sometimes irreversible damage.

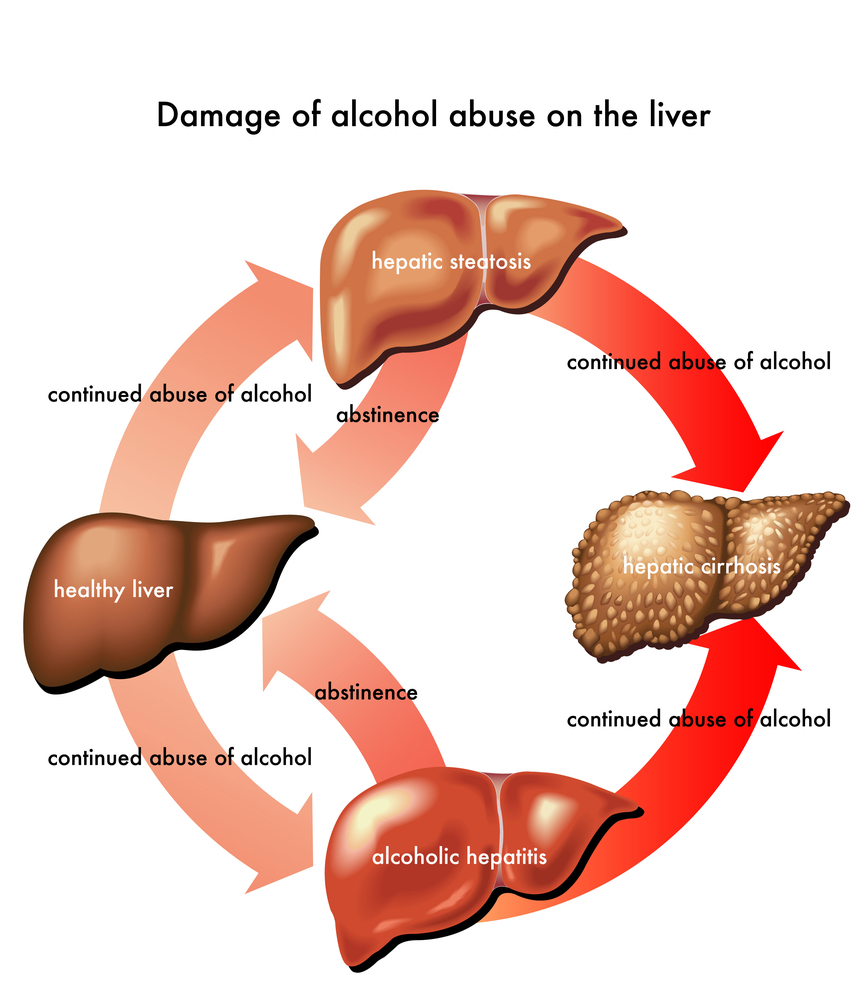

Just how alcohol damages the liver - and why it does so only in a minority of drinkers - isn’t entirely clear, although a number of hypotheses exist. It is known that the process of breaking down ethanol - the alcohol in beer, wine, and liquor - produces highly toxic chemicals such as acetaldehyde. These chemicals trigger inflammation that destroys liver cells. In time, web-like scars and small knots of tissue replace healthy liver tissue, interfering with the liver’s ability to function. This irreversible scarring, called cirrhosis, is the final stage of alcoholic liver disease.

Alcoholic Liver Disease

Heavy alcohol use can lead to liver disease, and the risk increases with the length of time and amount of alcohol you drink. But because many people who drink heavily or binge drink never develop alcoholic hepatitis or cirrhosis, it’s likely that factors other than alcohol play a role:

- Genetic factors. Having mutations in certain genes that affect alcohol metabolism may increase your risk of alcoholic liver disease as well as alcohol-associated cancers. Genetic factors may account for half of any person’s susceptibility to alcohol-related disease.

- Other types of hepatitis. Long-term alcohol abuse worsens the liver damage caused by other types of hepatitis, especially hepatitis C. If you have hepatitis C and also drink - even moderately - you are more likely to develop cirrhosis than is someone who doesn’t drink.

- Other diseases. People who drink alcohol are more likely to develop alcoholic hepatitis if they also have another disease that affects the liver, such as diabetes or iron overload (hemochromatosis) - a disorder in which the body stores too much iron.

- Obesity. Although most researchers agree that obesity makes alcoholic liver disease worse, exactly why this is so isn’t clear. It may be that alcohol causes fatty tissue to produce certain hormones and cytokines - immune system proteins that increase inflammation.

- Malnutrition. Many people who drink heavily are malnourished, either because they eat poorly - often substituting alcohol for food - or because alcohol and its toxic byproducts prevent the body from properly absorbing and metabolizing nutrients, especially protein, certain vitamins, and fats. In both cases, the lack of nutrients contributes to liver cell damage. It was once thought that malnutrition, rather than alcohol, caused alcoholic liver disease. Now, the relationship between the two appears more complicated. But it’s certain that drinking leads to malnutrition, which damages the liver and contributes to some of the serious complications of alcoholic liver disease.

Risk factors

- Alcohol use. Consistent heavy drinking or binge drinking is the primary risk factor for alcoholic hepatitis, though it’s hard to precisely define heavy drinking. Some experts believe that four or more drinks a day for men and two or more a day for women greatly increase the risk of liver damage. Moderate drinking is usually defined as no more than two drinks a day for men and one for women. But because people vary greatly in their sensitivity to alcohol, that amount may not actually be moderate for everyone. Whether certain types of alcohol cause more harm than others also is a matter of debate. Some experts believe that wine is less damaging than hard liquor is, although it may be that wine drinkers generally tend to have healthier lifestyles.

- Age. The effects of alcoholic hepatitis are most likely to show up after years of heavy drinking, but symptoms of the disease can develop in people as young as 20.

- Your sex. Women are two to three times as likely to develop the alcoholic liver disease as men are. It takes less alcohol to harm the liver in women, and when liver disease occurs, it progresses more quickly than it does in men. This disparity may result from differences in the way alcohol is absorbed and broken down. Because women tend to metabolize alcohol more slowly, their livers are exposed to the higher blood concentrations of alcohol for longer periods of time - with potentially greater toxicity. The slow rate of alcohol metabolism in women may be due to lower levels of stomach enzymes that break down alcohol, the effects of estrogen, or even the size of a woman’s liver.

- Genetic factors. Researchers have discovered a number of genetic mutations that affect the way alcohol is metabolized in the body. Having one or more of these mutations may increase the risk of alcoholic liver disease and liver cancer.

When to seek medical advice

See your doctor if you develop any of the signs or symptoms of alcoholic hepatitis, including severe fatigue. Often, fatigue may be the first indication of liver disease. Severe symptoms such as gastrointestinal hemorrhage or serious mental confusion require emergency care.

Screening and Diagnosis

Because there are more than 100 liver diseases and a wide range of factors that can cause them, including viral infections, drugs, and environmental toxins, diagnosing alcoholic hepatitis can be challenging. In addition to full medical history, including questions about your drinking habits and a physical exam, you’re likely to have certain tests, including:

- Blood tests. These check for high levels of certain liver enzymes: gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and alanine aminotransferase (ALT). Elevated levels of these enzymes are likely to occur in people with alcoholic hepatitis. You may also have tests to check for viral infections that affect the liver such as hepatitis B and C.

- Ultrasound. Your doctor may use this noninvasive imaging test to view your liver - in people with alcoholic hepatitis, the liver may be enlarged - and to rule out other problems such as gallstones or bile duct obstruction.

- Liver biopsy. In this procedure, a small sample of tissue is removed from your liver and examined under a microscope. Your doctor is likely to use a thin cutting needle to obtain the sample. Needle biopsies are relatively simple procedures requiring only local anesthesia, but your doctor may choose not to do one if you have bleeding problems or severe abdominal swelling (ascites). Risks include bruising, bleeding, and infection.

Complications

- Increased blood pressure in the portal vein. Blood from your intestine, spleen, and pancreas enters your liver through a large blood vessel called the portal vein. If scar tissue blocks normal circulation through the liver, this blood backs up, leading to increased pressure within the vein (portal hypertension).

- Enlarged veins. When circulation through the portal vein is blocked, blood may back up into other blood vessels in the stomach and esophagus. These blood vessels are thin-walled, and because they’re filled with more blood than they’re meant to carry, they're likely to bleed. Massive bleeding in the upper stomach or esophagus from these blood vessels is a life-threatening emergency that requires immediate medical care.

- Fluid retention. Alcoholic liver disease can cause large amounts of fluid to accumulate in your abdominal cavity (ascites). Several factors play a role in fluid buildup, including portal hypertension and changes in the hormones and chemicals that regulate fluids in your body. Ascites can be uncomfortable and may interfere with breathing. In addition, abdominal fluid may become infected and require treatment with antibiotics. Although not life-threatening in itself, ascites are usually a sign of advanced alcoholic hepatitis or cirrhosis.

- Bruising and bleeding. Alcoholic hepatitis interferes with the production of proteins that help your blood clot and with the absorption of vitamin K, which plays a role in synthesizing these proteins. As a result, you may bruise and bleed more easily than normal. Bleeding in the gastrointestinal tract is particularly common.

- Jaundice. This occurs when your liver isn’t able to remove bilirubin - the residue of old red blood cells - from your blood. Eventually, bilirubin builds up and is deposited in your skin and the whites of your eyes, causing a yellow color. Excreted bilirubin may turn your urine dark brown and your stools a pale clay color.

- Hepatic encephalopathy. A liver damaged by alcoholic hepatitis has trouble removing toxins from your body - normally one of the liver’s key tasks. The buildup of toxins such as ammonia - a byproduct of protein digestion - can damage your brain, leading to changes in your mental state, behavior, and personality (hepatic encephalopathy). Signs and symptoms of hepatic encephalopathy include forgetfulness, confusion, and mood changes, and in the most severe cases, delirium and coma.

- Cirrhosis. This serious condition, which is insidious and irreversible scarring of the liver, is the fourth-leading cause of death in Americans ages 45 to 54. Cirrhosis frequently leads to liver failure, which occurs when the damaged liver is no longer able to adequately function.

Treatment

Complete abstinence from alcohol is the single most important treatment for alcoholic hepatitis. It’s the only way to reverse liver damage or, in more advanced cases, to prevent the disease from becoming worse. Without treatment, the majority of people with alcoholic hepatitis eventually develop cirrhosis.

If you are dependent on alcohol and would like help, your doctor can recommend a therapy that’s tailored for your needs. This might be a chemical dependency evaluation, a brief intervention, counseling, an outpatient treatment program, or a residential inpatient stay.

Other treatments for alcoholic hepatitis include:

- Nutritional therapy. This is a crucial part of treating alcoholic hepatitis because malnutrition contributes to liver damage. A doctor or dietitian is likely to recommend a high-calorie, nutrient-dense dietary plan to help liver cells regenerate. Doctors also often recommend reducing dietary fat because alcohol interferes with the normal metabolism of fatty acids, leading to deposits of fat in the liver (alcoholic fatty liver). In some cases, medium-chain triglycerides may be prescribed as a supplement. This is a type of fat, found primarily in coconut oil, that may actually help reduce the buildup of harmful fats in the liver. Supplementing with vitamins and minerals depleted by alcohol - especially vitamins B1, B2, and B6 and calcium and iron - also is key.

- Lifestyle changes. Quitting smoking and maintaining a healthy weight can help improve liver function. Smoking has been shown to increase the rate of liver scarring in people with alcoholic hepatitis, and obesity contributes to fatty liver.

- Drug therapies. People with severe alcoholic hepatitis may benefit from treatment with corticosteroids to reduce inflammation and with pentoxifylline, a drug that prevents the body from making tumor necrosis factor-alpha, a powerful substance linked to inflammation. Other therapies that inhibit tumor necrosis factors also may be considered.

- Antioxidants. Harmful oxygen molecules called free radicals to play a major role in alcoholic hepatitis by causing extensive damage to liver cells. Treatment with antioxidants can help prevent this damage. The supplement SAM-e may be of some benefit. Other natural supplements, such as the herb milk thistle, also may be helpful. In Europe, milk thistle has been used for centuries to treat jaundice and other liver disorders. The chief constituent of milk thistle, silymarin, may aid in healing and rebuilding the liver by stimulating the production of antioxidant enzymes.

- Liver transplant. When liver function is severely impaired, a liver transplant may be the only option for some people. Although liver transplantation is often successful, the number of people awaiting transplants far exceeds the number of available organs. For that reason, liver transplantation in people with alcoholic liver disease is controversial. Some medical centers won’t perform liver transplants on people with alcoholic liver disease because they believe a substantial number will return to drinking after surgery, won’t take the necessary anti-rejection medications, or will require more care and resources than will other patients. Most of these objections have not been borne out in practice, however, and many doctors now feel that some people with alcoholic liver disease are good candidates for transplant surgery. But requirements are still stringent, including abstinence from alcohol for at least six months before surgery and enrollment in a counseling program.

Prevention

The only sure way to prevent alcoholic hepatitis is to drink very lightly or not at all. People vary greatly in their sensitivity to alcohol, and even occasional social drinkers may risk liver damage. If you have been diagnosed with alcoholic hepatitis, you should not drink alcohol again.

These measures may also help reduce your risk of alcoholic liver disease:

- Protect yourself from hepatitis C. Hepatitis C is a highly infectious liver disease caused by the hepatitis C virus. Untreated, it can lead to cirrhosis. If you have hepatitis C and drink alcohol, you’re far more likely to develop cirrhosis than someone who doesn’t drink is. Because there’s no vaccine to prevent hepatitis C, the only way to protect yourself is to avoid exposure to the virus. Most people with hepatitis C became infected through blood transfusions received before 1992, the year improved blood-screening tests became available. In rare cases, hepatitis C can be transmitted sexually. If you aren’t absolutely certain of the health status of a sexual partner, use a new condom every time you have sex. Don’t use nasal cocaine, and avoid sharing needles or other drug paraphernalia. Contaminated drug paraphernalia is responsible for about half of all new cases of hepatitis C. See your doctor if you have or have had hepatitis C or think you may have been exposed to the virus.

- Limit medications. Because your liver detoxifies and eliminates drugs from your system, most medications, including nonprescription ones, can damage liver cells. This is particularly true if the drugs are taken in excess or with alcohol. Be especially careful not to mix acetaminophen with alcohol - the combination can cause liver failure. Talk to your doctor about the effect on your liver of any medications you take.

Original Article: http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/alcoholic-hepatitis/DS00785

1998-2007 Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research (MFMER). All rights reserved. A single copy of these materials may be reprinted for noncommercial personal use only. "Mayo," "Mayo Clinic," "MayoClinic.com," "EmbodyHealth," "Reliable tools for healthier lives," "Enhance your life," and the triple-shield Mayo Clinic logo are trademarks of Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research.